Written by David Johnson

Photos by Jerry Monkman, EcoPhotography

Local dairy farms, once abundant and widespread, are dwindling. To understand their importance, look no further than a fixture in the New Hampshire dairy landscape - Scruton's Dairy.

The call came in at night.

The news on the other end was simple – and devastating. Artie had been in an accident. A fatal one. There was no one to work the farm the next morning. No one to milk the cows. Someone had to go to the farm and start working. Livelihoods were at stake.

There was no time to lose.

Scruton’s Dairy is an iconic dairy farm in Farmington, NH and one of the last vestiges of the booming dairy farm economy that had commanded so much of rural New Hampshire in the 20th century. As one of only four commercial dairy farms remaining in Strafford County, Scruton’s Dairy is both an agrarian artifact of what-once-was and a clarion call that all who care about locally produced consumables should heed; there aren’t many like Scruton’s around, and when these farms leave, they never return.

Then again, there weren’t many like Scruton’s Dairy even in the heyday. An iconic fixture of the Granite State agricultural topography for close to a century, the farm has been active for generations – and has even seen its physical location change over the years. At one time the Scruton family farmed the side of Blue Job mountain, until a fire claimed it in 1926. After that, Scruton’s found new life on its current parcel, which grew as the Scruton line added pieces of land, mainly to catch up with the needs of feeding the herd. Today Jason and Kerri Scruton operate the farm, along with their son Jacob and Jason’s sister Katherine.

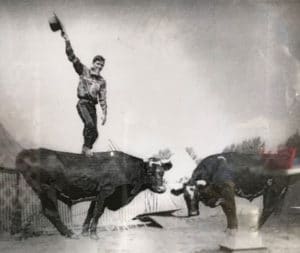

Frank Scruton – Jason Scruton’s grandfather – had been the lynchpin to the expansion, though operating a dairy farm had not been his original love. No, for Frank, it was vaudeville that beckoned him, as he was a fixture on the circuit with his trained steers; but World War II changed his plans and he eventually made the move from the stage to the stall.

Not that you could take the performer out of Frank Scruton, a legend on the 4H circuit who was known for showing trained oxen (he was even featured in Ripley’s Believe It or Not!). In 1946, Frank bought a truck and started delivering Scruton milk. Between the high quality of his dairy and the omnipresence of the Scruton name thanks to his showmanship, the farm flourished (one day during a particularly brutal snowstorm which made the roads impassable, Frank loaded up the day’s dairy yield on a truck that was then towed by a team of oxen to Rochester, NH - such is the time-sensitive nature of pre-pasteurized milk!).

Frank’s son Artie took Scruton’s to the next level by incorporating in 1972 and adding more land – a critical component to any dairy farm. As a herd grows, the need for land - to both generate corn and hay for food grows as well - every cow requires approximately two acres of open land. This symbiotic relationship between cow and country represents the healthy balance between the herd and maintaining the full productivity of the land that dairy farmers cherish – and require.

As Artie shepherded Scruton’s Dairy, his son Jason cut his teeth working on the farm before becoming a professional cow nutritionist, an esteemed and indispensable position in the world of dairy farming. Jason was building a great career at Blue Seal and Scruton’s Dairy was humming along – life was going according to plan.

Then one night the phone rang.

TIME IS OF THE ESSENCE

"The Scruton’s milk their cows twice a day,” said Jeremy Lougee, SELT’s Conservation Project Manager and Farmland Coordinator. “The cows and their bodies grow accustomed to this schedule, so there really isn't an option to take a day off. Similar to humans, if the cows aren't milked for several days in a row, their bodies get the message that milk isn't needed and they stop producing”

And if the cows stop producing milk, it’s game over. The farm will not last.

A walk around Scruton’s Dairy is like a stroll through the circle of life (Holstein edition), and every phase must snap together seamlessly if the operation is going to be a success. First, a series of small shelters house the calves, the Scruton rookie class; second, is the enclave where the heifers hang out, learning the ropes; third, are the heifers and cows, preparing to give birth, waiting on the bench and ready to get called up to the majors; and, finally, The Show, where the milk flows and a livelihood is forged.

And so the wheel turns – cows are birthed, cows grow up, cows give birth to other cows, cows are milked (twice a day), and on and on. The wheel never stops because if it did, even for one day, as Kerri Scruton says: “Would you want to go a day without eating?”

The cows certainly wouldn’t.

Tending the herd is so much more than an adventure in biology. A dairy cow generates over 13 tons of manure a year. Multiply that by 200 – the size of the Scruton herd – and you’re dealing with nearly fourteen-hundred Buick Regals worth of cow manure to return to the holistic balance of nature . Again, the circle of life kicks in at this point, as the manure is used to fertilize fields that will produce hay and corn and fermented feed (that is, feed preserved for the winter months).

“The remaining dairy farmers in New Hampshire are the absolute cream of the crop,” says Jeremy. “Every single day of the year, they’re producing in an extremely unstable dairy market while still doing an impeccable job to maintain a healthy environment for the cows and the surrounding landscape.”

A FARM FOREVER

Large swaths of land are key to a dairy farm, and with that Kerri and Jason made the move to work with SELT and conserve their farmlands for perpetuity.

“Jason and Kerri literally saved this farm,” Jeremy says. “And the easement now ensures this land will be protected and available for the generations to follow.”

“SELT has been so patient and understanding with us,” Kerri said. “It was important to us because it’s a guarantee the farm will still be here. When these farms go away, you don’t get them back.”

That is not hyperbole. The dairy industry in New Hampshire has declined precipitously over the years. In the past decade, New Hampshire has lost over a third of its dairy farms.

"When these farms go away, you don’t get them back."

And Kerri is right - once they go away they don’t come back. And when the local dairy producers leave, suddenly there is a whole lot more pressure on outside providers to generate the milk supply, the Granite State loses the control and security from a locally-produced product, and expenses rise as transportation costs balloon.

“All of this goes to show that we must support and protect our remaining dairy farms in New England,” says Jeremy.

Of course, fresh milk doesn't travel well, and the further away those providers are, the less fresh it becomes. Hence the critical importance of local.

It’s late morning at Scruton’s Dairy. Kerri has brought out a photo album documenting the rich history of the Scruton family tree. There are pictures of Frank astride his trained oxen, photos of 4H presentations, and shots of the farm in its various iterations over the century it’s been in operation, providing high-quality milk to the Granite State.

The farm is active - as it always is, every day, nearly around the clock. It never stops. It can never stop.

A large milk truck pulls out of the driveway. It is filled with Scruton’s best, directly on its way to the Hood milk plant in Concord to be pasteurized and bottled and distributed throughout the region; when it comes to milk, the clock starts as soon as the milk fills the tanker. It is the cost of freshness.

This milk truck - and others like it- carry the weight of livelihoods and legacies, for Scruton’s Dairy and the precious few other dairy farms in New Hampshire.

There is no time to lose.