Written by David Johnson

Photographed by Jerry Monkman - EcoPhotography

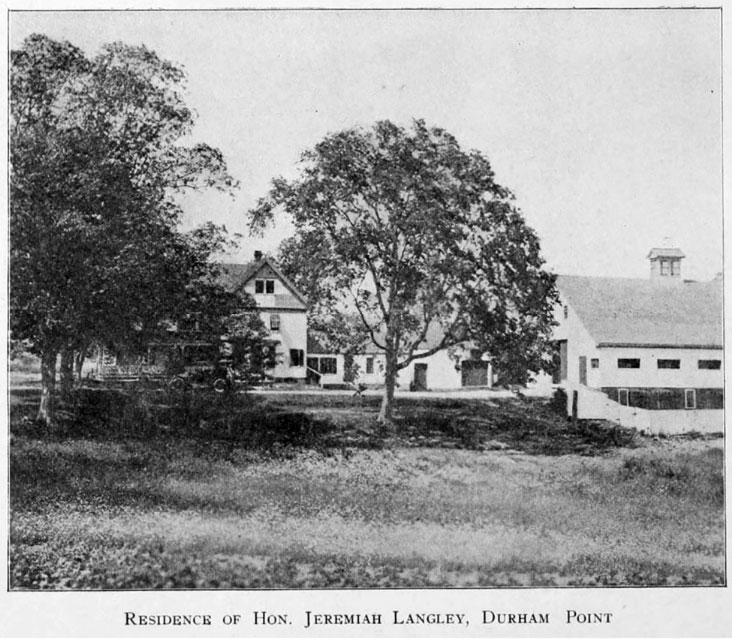

Hewn into the original timbers of the Langley farmhouse and sown in the sands and soils of the land where it sits, is the story of multiple generations branching from a family tree whose roots spread deep through Durham, NH.

There were no idle hands at the Langley family’s historic homestead in Durham. For a young Pamela Langley, there was always something going on at the farm, always something to do. From haying to growing Hubbard squashes to tending to beef cattle to their eventual focus on dairy farming, the Langleys’ property was perpetually buzzing.

“I had my little cow chores where I had to feed the calves,” Pamela says. “And then when the cows separated, it would be my job to go bring those cows back. I would walk about halfway down, and I'd holler, ‘Come on, cows!’ and they would actually come. It was a pretty nice skill to show off.”

That was the life Pamela was born into, and she wouldn’t trade it for the world. And as she approaches the finale of a conservation conversation that began with SELT over five years ago, the prospect of seeing her beloved family land protected forever represents the perfect coda on a historical record that spans centuries.

“After I retired, I had more time to think about conservation,” Pam says. “As I would talk to my mother, she would say, ‘Don't forget to put the land in conservation.’”

During the early colonial period, Durham Point (which is encompassed by the Langley property) was an important locus, offering a variety of landing points for seafarers.

During the early colonial period, Durham Point (which is encompassed by the Langley property) was an important locus, offering a variety of landing points for seafarers.

The adjoining Bickford Point served as one of the first ferry landing posts, operating from the mid-1600s until the late 1700s, with the route ending at the end of Langley Road. Before there was the Scammell Bridge crossing Little Bay, this was the primary way to move goods and people across Little Bay.

Teams of oxen were stationed along a small hill off of Durham Point Road and would be used to unload the laden ferry, but the only remnants are the name “Team Hill” and a network of stone walls.

“My ancestors have been on this property since the 1600s,” Pam says.

Her great-grandfather, Jeremiah, was a prominent Durham citizen, active in state and local politics who made his name operating coal barges from Portsmouth to Dover, Exeter, Durham, and Newmarket. Successive generations took more to farming, and the milieu’s agricultural activity kept everyone busy - until their circa 1700s-built historic barn burned down in 1981.

“It was such a loss,” Pamela recounts. “We had one phone in the house at the time and if it rang in the night, I was the one expected to answer it. Usually, it was a drunken college student.”

Not that time. A “sober-sounding lady” asked to speak to her father Stanley, who picked up, listened quietly for a bit, hung up, turned towards the family and with the most deadpan Yankee delivery imaginable calmly said: “Barn’s on fire.”

Thankfully, no livestock were in the barn at the time, but the edifice’s charred cinders represented a significant chapter break for the Langley story. Commercial farming had come to a close. From then on, it was a vegetable garden here and there and third-party haying to keep the fields open.

Because of its heritage, Pamela envisions her family’s farm to continue to add value to the local agricultural landscape, which is made possible thanks to the looming conservation of her family’s 44+ acre property.

Fried eels. Who knew?

When she wasn’t wrangling lollygagging cows or blistering her hands hauling hay bales, Pamela could, alternatively, be found on the shores of Oyster River, scavenging the brackish waters in her backyard for horseshoe crabs to use as bait for eels.

“We'd chop them into sections and roll them in a little cornmeal and flour and fry them up,” she says.

The magic of the Langley spread is its geographical diversity, and Pamela pursued every aspect that the varied biomes had to offer. It was a surf and turf upbringing.

And while the property’s soil-centric farming may have receded, today there is an important, modern form of agriculture – aquaculture - that remains: oyster farming. The reefs located at the mouth of the Oyster River are rich in shelled bounty.

“Of the 15 active oyster farms in New Hampshire, 14 operate in Little Bay with four operating off of Durham Point and in close proximity to the Langley Project,” says Steven Jencso, Coordinator of the NH Shellfish Farmers Initiative. “With the limited coastline of New Hampshire, and the extreme development pressure in the fastest growing region of the state, conservation of the Langley property serves to protect water quality that these farms and the estuary depend on.”

Created in 2015 and supported with a significant investment from the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation’s Great Bay Watershed Fund, Great Bay 2030 coordinates local, state, and federal resources to restore critical habitats, enhance water quality and quantity, encourage adaptation and resilience in the face of a changing climate, foster a culture of stewardship, and, of course, conserve priority lands.

“The protection of the Langley property is a tremendous addition to the landscape of conservation lands on Durham Point and along Great Bay,” said Dea Brickner-Wood, Great Bay Coordinator for the Great Bay Resource Protection Partnership. “Identified in the NH Coastal Watershed Conservation Plan as a priority conservation area, this historically significant property boasts many conservation attributes including high value agricultural resources, wildlife habitat, and undeveloped shoreline along Great Bay and the Oyster River.”

It doesn’t get much more “priority” than the Langley property. And that’s reflected in the federal granting programs that have stood behind its conservation. The importance of the Langley property shows through the multitude of partnerships supporting its conservation. One is the NH Source Water Protection Partnership which is funded through the US Natural Resource Conservation Service’s Regional Conservation Partnership Program (RCPP). This Partnership is seeking protection and restoration of lands and water in critical watersheds across New Hampshire, and the Langley project was awarded a $1,076,000 grant.

And in September, SELT’s partner, the Strafford County Conservation District, was awarded $1,131,500 by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). The Conservation District successfully applied for and secured the NOAA funding and will co-hold the conservation easement with SELT. These two grants, plus $100,000 from SELT’s Conservation Acceleration Fund, will ensure the future of this critical land.

“Our partnership identified Pam’s property as a critical area for enhancing and safeguarding wildlife habitats and intertidal areas,” says Duane Hyde, SELT’s Land Conservation Director. “In addition, the conservation easement enshrines permanent conservation to a scenic stretch of river visible from several public locations like Durham’s Wagon Hill Farm, Newington’s Fox Point and the Scammell Bridge. When you take the heritage value of this land into consideration as well, you’re looking at a generational opportunity to preserve the shoreline for the benefit of both the human and natural communities of Great Bay.”

Pam sits at her kitchen table and recounts her childhood adventures. She remembers the halcyon days of hay hustling, the bovine detective work, the lobstering with her dad, or the lazy afternoons walking through the woods.

The accumulation of these memories, added to the already sprawling family history, fashions a tome of local legend.

And if some day in the not-so-distant future, you find yourself on the shores of the Oyster River at Durham Point or looking across the river from Wagon Hill, breathe deep the salt air and gaze at the ghosts of the Bickford Point ferry landing and soak up the story yourself.

Preferably with fried eel.