Written and photographed by David Johnson

When thoughtful stewardship meets cutting-edge science, new frontiers are revealed.

The forest is quiet. A faint breeze meanders through the overstory, shifting branches ever so slightly, jarring loose a handful of the first leaves that are ready to jump ship in the face of the approaching New England autumn. A man is walking the trail that weaves through the woods—and pauses. Something captures his eye.

He peers into the knot of timber and brambles just off the beaten path. There it is. He would have missed it if not for the briefest glint of sunlight ricocheting off its silk strands.

A spider web.

The man veers off-path and tentatively approaches the web. It’s at ground level, which is ideal for his purposes. He draws closer and sees more detail. This has promise. The web looks recently spun, fairly free of the woodsy refuse that can get entangled in the silk after a long period of disuse.

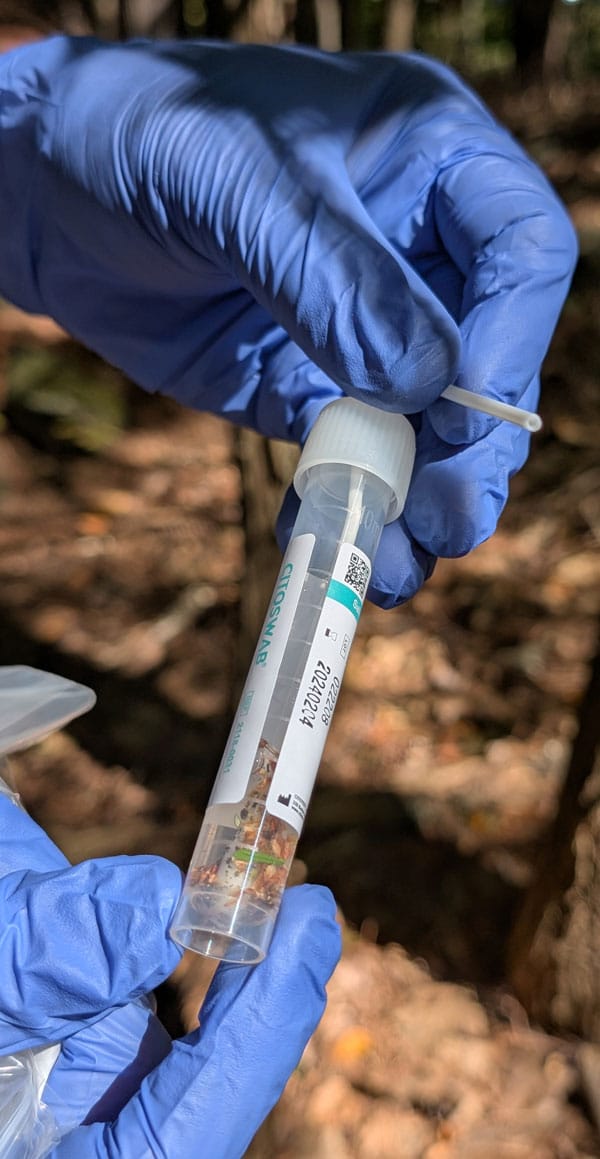

He retrieves a pair of blue nitrile gloves from his back pocket and slides one on each hand. Then he takes out a baggie containing a clear plastic tube and a cotton swab. Deftly, he spins the swab on the web, twisting it in the gooey gossamer as if he were spiraling spaghetti on a fork.

Confident in his sample, he puts the swab in the tube, the tube in the baggie, takes off his gloves, and departs the scene. He got what he came for. A clue. A puzzle piece. A snippet of a clause, of a sentence, of a paragraph, of a million-page novel written in DNA that has a very important question to ask the forest:

Who goes there?

The University of New Hampshire

Durham, NH

9:48 a.m.

As I approached Gregg Hall, I didn’t quite know what to expect. My tenure as a post‑grad writing student came to a close three years before this building came online. Not that it would have mattered; Gregg Hall is a science and research building, stacked with advanced lab equipment that would look at home on the bridge of the Enterprise. The last thing anyone wants is a flaky English major wandering through a lab, lost in thought about dangling participles while knocking over flasks of acid.

So, it was with a hefty amount of anticipation that I, said former English major and perpetual acid flask risk, took the staircase to the second floor to meet with Dr. Jeffrey Miller, Research Assistant Professor in the Department of Molecular, Cellular, and Biomedical Sciences.

The subject of the conversation: a new frontier in DNA research that inventories the wildlife community passing through forest habitat. Capturing segments of Environmental DNA (eDNA) and sequencing species‑specific DNA barcodes, researchers are able to identify the diversity of wildlife in the area, a gold mine of intel for conservation and land management organizations like SELT.

“Generally speaking, eDNA is any DNA that ends up in the environment that you can sample and sequence to identify who it’s coming from,” Jeff says. “You can find it in anything from a water sample to track microbes to the surface of leaves in a forest to see what’s been walking through.”

“The eDNA process takes a lot of cues from working a crime scene,” Jeff says. “We’re essentially talking about finding any small traces of DNA from all the things that might’ve passed through a particular area.”

Jeff got rolling as an undergrad in Minnesota, pursuing fish research and evolutionary biology. This cultivated an interest in a deeper dive into the molecular goings‑on of aquatic species, which led to even deeper dives into the world of DNA. Soon enough, he had developed a real knack for coding and analyzing cosmically complex DNA sets.

He began at UNH working with Alison Watts, Research Assistant Professor for Civil and Environmental Engineering (and SELT Board member), using the eDNA tactic in support of a large estuaries project that monitored fish populations. This was all new stuff—something UNH was pioneering—and its proof‑of‑concept eventually made the jump from the aquatic realm into the terrestrial world. Jeff was now trading his waders for hiking boots and bug spray.

That’s where the spiders come in.

Spiders create their webs from silk—a remarkably engineered, lightweight material produced by specialized glands on their abdomen. They methodically weave the structure using a durable, non-sticky form of silk. Once that phase is complete, they deploy a spiral of glue-like silk from the outside, trapping unsuspecting insects.

Now, with the dawn of eDNA, web functionality has taken on a new dimension, becoming more than all-you-can-eat bug buffets and turning into repositories for trace DNA.

“Webs are useful because air is passing through them at all times,” Jeff says. “It’s almost like setting up a passive filter in the woods to continuously sample the air. And then we take all the stuff that might have accumulated, bring it back, and see what animals it might have come from.”

This approach kicked off in 2023 in Australia, when scientists sampled webs outside an open-air zoo to see if they could match eDNA to nearby animals. Stateside, this is all new, and Jeff and UNH are at the forefront of testing its viability in forests and ponds.

Which is where organizations like SELT come in. As one of the largest private landowners in the region (nearly 12,000 acres and counting), SELT provides a unique portal to eco-researchers like Jeff, offering diverse venues to investigate with eDNA capture. The opportunity to partner with UNH came via Board member Alison Watts.

“As a researcher, it is very rewarding to work with a land trust like SELT, where our science can be applied to real-world landscapes to better protect and preserve habitat,” she says. “SELT’s Strategic Plan calls on the organization to ’sustain ecological functioning for natural systems, wildlife, and the health and well-being of all people,’ and eDNA is one of the most exciting new methods to help us actually measure if we are succeeding in our mission to sustain natural systems.”

“Leveraging our lands to further advances in research is an important component of our stewardship goals,” says Deborah Goard, SELT’s Stewardship and Land Engagement Director. “It’s exciting for us to be at the forefront of a project that can inform our land management practices in new ways.”

The University of New Hampshire

Durham, NH

11:12 a.m.

We take a tour through the labs on the fourth floor, where the real eDNA magic happens. Actually, it’s the opposite of magic. It’s trillions of bits of data being fed through machinery with cool names like the Oxford Nanopore GridION, turbocharged by the on-campus supercomputer.

Jeff holds up a plastic pipette (fun fact: eDNA swabs are repurposed COVID test kits). The translucent tube contains clear liquid. Within that solution reside microscopic eDNA shards—the trace evidence washed and scrubbed from a gooey knot of spider web, dirt, and bark bits.

The sample is then placed in a machine with another cool name: the thermocycler, which essentially acts as a space-age Xerox machine, creating many copies of the short sequence for the various DNA that are found in the sample.

“Since eDNA is in such low concentrations, we have to amplify it,” Jeff says. “We’re making more and more copies of the DNA fragments because the instrumentation upstairs needs a little bit more starting material than just a single piece of DNA.”

Fascinated, I probe for more. “Wasn’t this the plot to Jurassic Park?” I think, unwilling to say it out loud so I don’t come across as a total nimrod.

Jeff indulges my curiosity: “We put the sample in with an energy compound, almost like sugar, and then add in raw DNA that hasn’t been put into a chain yet. We introduce a couple of other enzymes, and the machine heats up and cools, heats up and cools. That’s what thermocycling means. And that leads this chemical reaction to happen over and over again, where it’s running over the chunks of DNA that you have in the solution and making duplicates.”

An early-onset popsicle headache begins to manifest, so I call it.

But I actually kind of understand: what Jeff and his crew are doing is essentially trying to assemble a puzzle from the tiniest of pieces, amplifying them so they’re large enough to look at, and numerous enough to piece together the larger picture.

"As a researcher, it is very rewarding to work with a land trust like SELT, where our science can be applied to real-world landscapes to better protect and preserve habitat."

Of course, with that analogy, you’re talking about a puzzle with millions of pieces. Oh, and every puzzle piece has just one of four letters on it: A, C, G, or T. Assembling that monster puzzle? Now you’re getting to the heavy-hitter.

The DNA sequencer, one floor up, leverages the horsepower of the campus supercomputer, taking these amplified fragments and applying immense graphics processing power to piece together the eDNA clues and assemble cohesive strands of adenine (A), cytosine (C), thymine (T), and guanine (G), the four nucleotides that govern genetic coding and the structure of DNA.

The end result of this space-aged number-crunching is a .TXT document. But the As, Cs, Ts, and Gs are now ordered and—voilà!—Jeff has completed the puzzle. The newly assembled data strings are called “barcodes” and are not dissimilar to the ones on your Pringles can.

Or, if you want to shift your gaze to non-animals, you can get barcodes for fungus or plants. As long as the barcodes match the ever-growing DNA database, the flora and fauna inventory takes shape. These databases are publicly available due to efforts from places like the Smithsonian and NIH/NCBI, which you can find at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/refseq.

Music to the ears of a stewardship director at your friendly neighborhood land trust.

“The information that can be retrieved by eDNA has tremendous potential for informing our land management approach,” says Deborah Goard, SELT’s Stewardship and Land Engagement Director. “A more accurate idea of the diverse wildlife on our properties, especially those that are rarely seen, will lead to even more precision in our stewardship.”

The reference databases are still being built. The samples are still being collected. The barcodes are still being crafted. The science is still being refined. Jeff notes that he tries to “triangulate” his eDNA work by collaborating with other researchers at UNH like Remington Moll, the director of the Wildlife Modeling and Management Lab that specializes in camera work, and Dr. Laura Kloepper, lead of the Ecological Acoustics and Behavior Lab for acoustic monitoring.

“We’re trying to use all three methods at once to see if these newer technologies can give us better information,” he says. “That’s why we’re partnering with SELT. If we sample beforehand—before a management plan is put in place—does the extra bit of data on what species live there affect that management plan?”

The University of New Hampshire

Durham, NH

11:48 a.m.

We’ve just emerged from a quick trip down the nearby UNH trail. Jeff showcased a how-to on the notably analog eDNA capture process. Grab the Q-tip and twirl—and you’re in business. The pipette now holds a mass of grubby silk and leafy bits. It doesn’t look like much.

But soon enough, this nondescript wad of organic detritus will be scrubbed, washed, filtered, juiced-up, superheated, supercooled, superheated, supercooled, superheated, supercooled, multiplied, enlarged, then analyzed with enough computing power to send Michael J. Fox back in time.

And after all that, what comes out?

A series of letters that will change our understanding of the natural world.