Written by David Johnson

Photographed by Jerry Monkman

Great Bay 2030 marshals the combined power of the local conservation community to protect and steward the eco-engine of the Seacoast.

It’s a clear summer day on the New Hampshire Seacoast, and you’ve decided to walk a trail along the Great Bay. As you scan across the bright blue horizon line, you notice an osprey hovering about 40 feet above the water, before it darts down into the water to snap up an unsuspecting fish. Luckily, you happened to have your phone out and you snapped a photo just in time. You quickly take a look; not bad!

In the fraction of a second it took you to take the photo, your phone focused the lens, the aperture determined the amount of light that reaches the sensor, the shutter calculates how long the sensor is exposed to light, the sensor then captures the image, the phone’s hardware processes the image by placing each pixel’s readings in the correct spot and interpolating the missing values between the pixels. Voila - a cool photo of an osprey to share with your friends.

All those machinations under the hood are rarely considered and the workings of modern-day technology can easily be taken for granted. On a far more analog level - but no less complex - is the ecology Great Bay estuary itself, an infinitely sophisticated environment that features an intricate lattice of interdependent forces of nature (there’s a saying in the conservation world: “Ecology, it ain't rocket science, it’s a whole lot harder than that.”)

The Great Bay estuary is one of the largest on the Atlantic Coast, and encompasses the Great Bay itself, Little Bay, and the Piscataqua River, among many other bodies of water along the Seacoast. An estuary is where the salt water of the ocean meets the fresh water of rivers and streams, and the Great Bay watershed - the surrounding land where runoff water travels and eventually flows into the Bay, and ultimately, the Atlantic - is massive. The Great Bay watershed covers 1,000 square miles in New Hampshire and Maine, and over 400,000 people reside in 48 cities and towns within the watershed.

“The Great Bay estuary is the whole package of social and ecological services,” says Trevor Mattera, Habitat Program Manager for the Piscataqua Region Estuaries Partnership. “It is home to important habitats like eelgrass meadows, mud flats, and salt marshes, provides critical coastal resilience protection, houses many species of birds and wildlife, and supports fisheries that we rely on. These are the kinds of resources that you may not notice until they’re gone.”

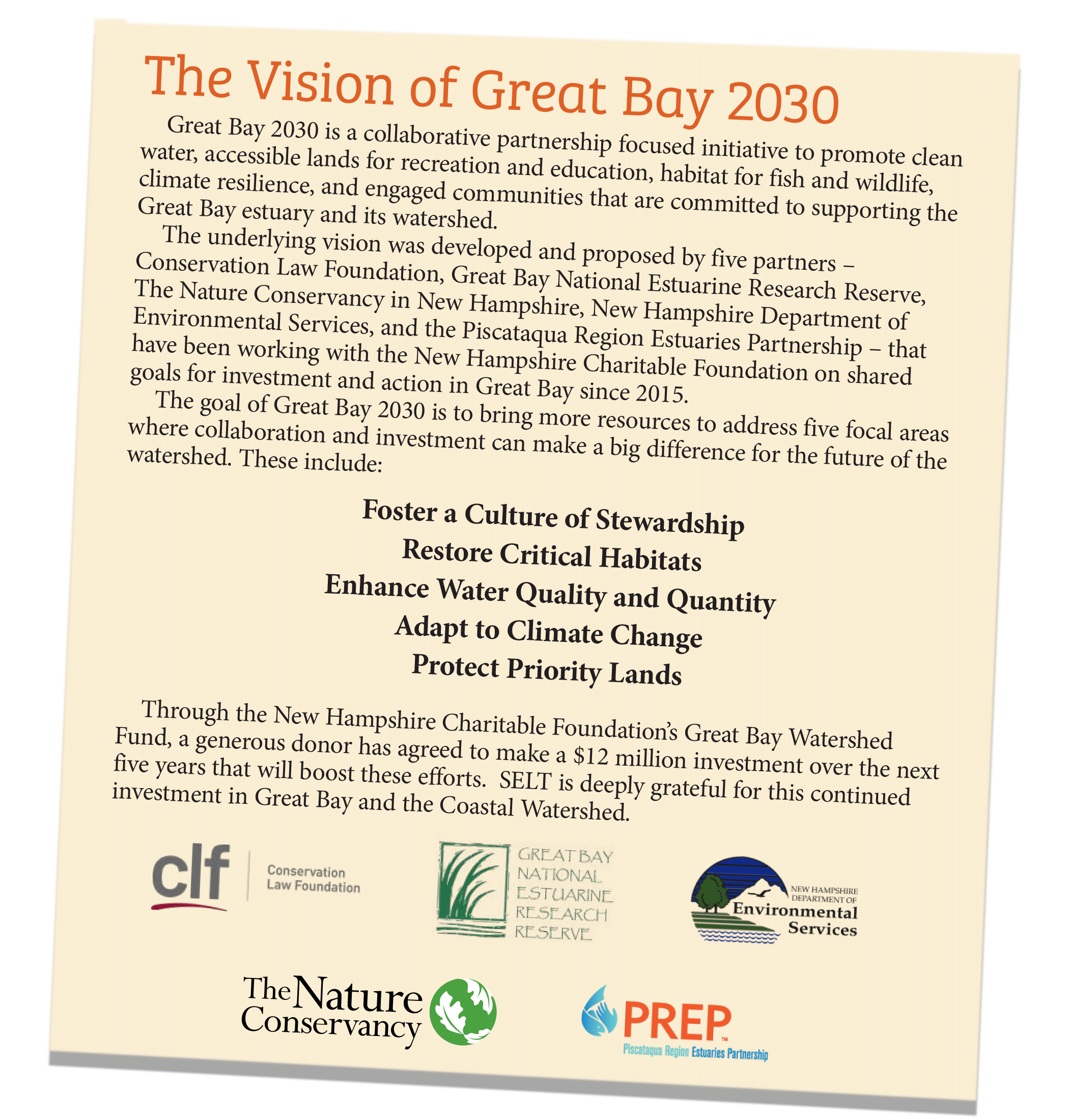

Which is why Great Bay 2030 was born. This broad, collaborative initiative is powered by $12 million in philanthropic giving through the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation’s Great Bay Watershed Fund. The vision of Great Bay 2030 (see side bar) represents a full-court press of local conservation and coastal organizations to protect and steward the estuary. The pillars of the project are five-fold: foster a culture of stewardship, restore critical habitats, enhance water quality and quantity, adapt to climate change, and protect priority lands.

“Great Bay 2030 is an absolutely huge opportunity to move the needle on estuarine health for the ecosystems and the people residing in the watershed,” Trevor says.

When it comes to watershed health, SELT’s role in the collaborative is especially important and why we are a key partner in Great Bay 2030 through SELT’s role as a member of the Great Bay Resource Protection Partnership (Great Bay Partnership). In fact, a new position, funded in part by Great Bay 2030, will be joining the SELT team this year; that person’s focus will be on the pro-active critical land conservation work within the estuary’s watershed.

“Great Bay 2030 is an absolutely huge opportunity to move the needle on estuarine health for the ecosystems and the people residing in the watershed.”

“In this watershed, SELT is the biggest regional land trust and one of the most important players out there,” Trevor says. “The person who takes this position will work with all the partners to protect the priority parcels that help water resources, marsh migration, habitat continuity, and water quality.”

“Although employed at SELT, the new land conservation position will really take their priorities and direction from the nine-member Great Bay Resource Protection Partnership,” says Duane Hyde, SELT’s Land Conservation Director. “This is based on a model that was successfully employed in the early 2000’s when hundreds of acres of critical Great Bay estuary watershed land were conserved through a concerted effort of the Partnership. We wouldn’t be able to reboot this effort without the support of Great Bay 2030 through the New Hampshire Charitable Foundation, The Nature Conservancy, and the Piscataqua Region Estuaries Partnership.”

Trevor says: “When it comes to what you can do to increase the health of your watershed and estuaries, land conservation not only protects critical terrestrial habitats, but it really is your best bang for your buck to protect water quality. That is why we need SELT at the table.”

And so, the work begins. The science has been done, the goals are on paper, and the partners have been assembled. The major players of coastal protection have assembled with a common goal: to protect one the region’s most important natural resources, a circuit board of advanced ecological systems all working together - sometimes out of sight and often out of mind - but always in service of the health of coastal lands we value the most.

“Great Bay 2030 is not top-down focused,” Trevor says. “It is built from all partners around the table. We know each other. We partner together. And now it’s time to get the work done.”